The memory of Heeramandi is still fresh, and Netflix has launched another historical movie with a brilliantly flawed feminism.

In the new Netflix film Maharaj, young Karsandas Mulji declares his feminism within five minutes. Karsan, 10, asks his father why ladies must always hide their faces while walking home from the temple. Later, he boldly advocates widow remarriage. In the 1860s, Karsan becomes a journalist in ‘Bombay’ after being born in Gujarat. He seems to spend his life improving the world for women. Perhaps Babil Khan punched a hole in the wall, asking why he wasn’t cast.

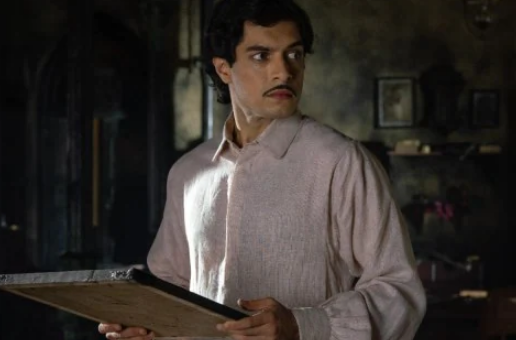

Another nepo-baby beat him. Junaid Khan, son of Aamir Khan, debuted in Maharaj. While it’s based on a landmark court case, it’s a biopic, and its politics seem above reproach, the finished film doesn’t show a single progressive bone. After Ranbir Kapoor’s Vijay in Animal, Karsan is Hindi cinema’s biggest red flag protagonist.

Although virtue signalling—which Karsan performs almost exclusively—is questionable, it is not a crime. His words and actions contradict one other. He proposes to Shalini Pandey’s Kishori, who is introduced with a song and dance. Not like the ‘item number’ Kriti Sanon’s character was introduced with in Mimi, another faux feminist film, but at least one male leers at her. Jaideep Ahlawat plays Maharaj, a village priest. Apparently delighted by her dance performance, the Maharaj invites Kishori to his rooms for an initiation ritual. She complies because her community convinced her it was a holy rite of passage. However, the Maharaj rapes her in public.

Karsan walks upon the scene—the movie has established that he’s annoyingly progressive—and shames Kishori, not the Maharaja. It’s shocking, but you wait, hoping the movie is setting up a redemption arc or third-act metamorphosis. Redemption requires admitting a moral transgression. Maharaj—naming it after the villain should have been a clue—seems unaware that Karsan is a bad person.

“Tumse yeh ummeed nahi thi,” he informs Kishori, cutting all ties. After witnessing her assault, this is his initial thought. Karsan may be the lone city resident unaware of the Maharaj’s crimes. He publicly shames her after comparing her to leftover food. They get so heated that Karsan almost slaps her in the face but stops himself. He’d get away with it in court, but we all know that a man who considers beating a woman is the same as one who does. A progressive film is rare.

Maharaj’s tangled morals is revealed when a random man informs Karsan that Kishori must be provided “sudharne ka mauka” now that she recognizes her “galti.” This simply reinforces the myth that Kishori caused her problems. We never see Karsan apologize for accusing her of betraying him. He claims that his support for “stree shikshan,” “ghunghat par rok,” and “vidva punarvivaah” has angered his conservative family, who are preparing to reject him. They call it “ghatiya vichaar.”

Just when you think Maharaj can’t get more absurd, it uses the worst stereotype. Kishori jumps into a well to commit suicide after being mistreated by her lover in public. A sexist pop-culture cliché dubbed ‘fridging’ involves maiming or killing female characters to motivate male characters to change. Maharaj perfects this theme, and Kishori dies in disgrace.

Karsan decides to write about the Maharaj and expose him as a creep after her death. The movie delays the court case we were promised in the beginning for 20 minutes. He starts a fresh relationship with Sharvari Wagh’s Viraj first. Within 15 minutes following Kishori’s death, the movie found a replacement, disrespecting her memory. Not that he ever regretted her loss.

Viraj, who sounds like Hansa from Khichdi, storms into Karsan’s office searching for job. Despite his vows to encourage women, Karsan acts like a red flag when an opportunity knocks. Viraj is hired, but she must labor for free. What is exploitation if not this? Even worse, the movie doesn’t realize that this minor detail pushes its protagonist farther into irredeemable terrain (as if abetting suicide wasn’t enough). Maharaj ignores the priest’s abuse of many women, as usual. Besides being titled after the villain, the film tells the story from a male perspective. Even the climax trial session centers on Karsan, whose pick-me attitude suggests he secretly passed the bar exam and become a barrister.

Hindi films frequently suffer from this perspective problem. Shalini Pandey was disregarded in Jayeshbhai Jordaar, another YRF film she could have starred in. However, Maharaj is more like a second cousin to the Manoj Bajpayee-starrer Sirf Ek Banda Kaafi Hai, a courtroom drama whose title should convey its sexism. Remember that “sirf ek banda” never suffices. Bollywood must realize that empowering female characters starts with not disregarding them.